A howitzer boomed and jets zoomed overhead as hundreds of spectators gathered to celebrate the opening of the second span of the Interstate 5 Bridge.

The year was 1958, but the ceremony, replete with World War I-era cars leading the crossing, much resembled one 41 years earlier, when the original span opened. Even Eleanor Holman and Mary Helen Kiggins, the two girls who unfastened the ribbon of the first span, now grown, were on hand to cut the ribbon on the second.

Barely a cloud in the sky, the temperature in the high 70s, it was a perfect July day. But one issue hovered over the jubilation: The prospect of charging tolls to pay for the new bridge.

Vancouver Mayor Irving Jensen faced the crowd, like E.G. Crawford, his predecessor nearly 55 years earlier, and argued the bridge should remain toll-free.

Hope metaphorically hung in the air in the form of the Federal-Aid Highway Act, a once-in-a-generation investment in infrastructure that President Eisenhower had signed two years earlier and which had created the Interstate Highway System. Perhaps, many speculated, some of these federal dollars could go to pay off the bonds and avert tolls.

Although traffic was just minutes from rushing across the bridge on that celebratory day, Jensen had time. Tolls were not scheduled to be imposed for the second time until after a retrofit to add a hump to the original span was completed, scheduled by the end of 1959.

Enlarge

The Columbian archives

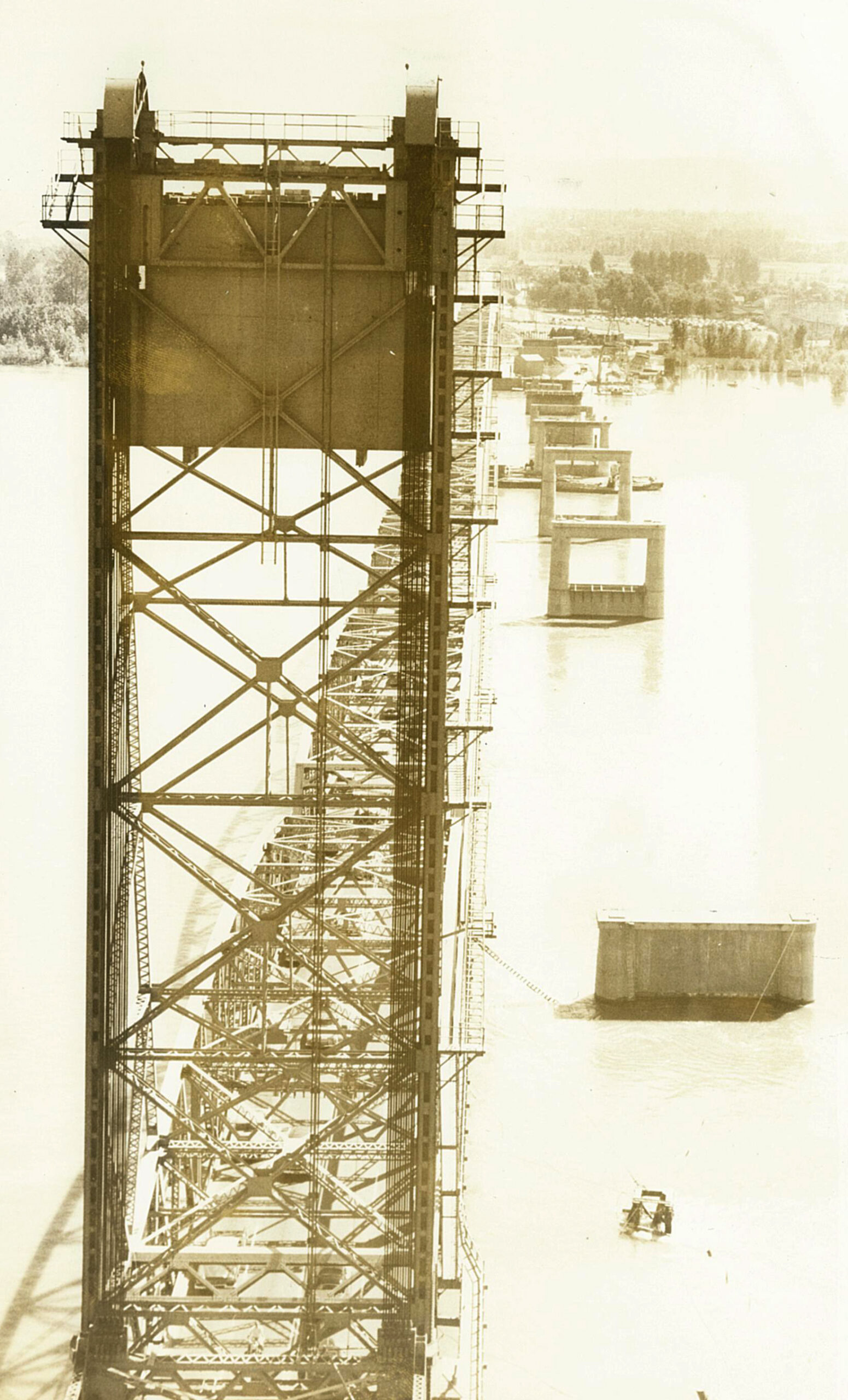

Need for something new

By 1948, it was clear the original bridge was not serving the region well. The more than 30,000 vehicles that crossed it daily exceeded the bridge’s capacity, and widening the existing structure was out of the question.

But a solution was unclear.

Regionally important, the bridge was the only connection over the Columbia River between Vancouver and Portland. It was nationally significant, as well, connecting Canada with Mexico. More than half of the tourists who visited Washington via automobile entered the state by way of the Interstate Bridge.

If that connection were cut, it would be dire for the region.

R. H. Baldock, Oregon’s chief highway engineer, was the first to plant a seed for a new crossing. Although the idea had not been officially taken up by Oregon or Washington’s highway commissions, growing congestion was prompting the need for action. Baldock proposed a second span next to the original.

Surveying for a new bridge started in May 1950. By October, a joint proposal by the Oregon and Washington Highway departments called for a new bridge near the original. According to the proposal, all southbound traffic would use the new span and all northbound traffic would use the existing span. The logic was that a new bridge close to the existing span would require fewer piers and therefore cost less than other options.

It was by no means a final decision, however. In June of the next year, the highway departments proposed four potential locations for a new bridge: Two east of the current span and two west.

One would connect Northeast 85th Avenue in Portland with the Evergreen Highway about four miles east of Vancouver — roughly where the Interstate 205 Bridge is today. Another would connect Northeast 33rd Avenue in Portland with the Evergreen Highway about one mile east of Vancouver — near the Portland International Airport and today’s Columbia Business Center.

The two options west of the bridge were next to the Interstate Bridge and one connecting the St. Johns area of Oregon with the opposite Washington bank.

The idea of a tunnel near the railroad bridge was also floated, as it was originally thought to cost less and not affect river navigation, so much so that representatives from Clark County spoke at the St. Johns Tunnel Club. But further studies put the cost of a tunnel at $62 million, many times more than a new span.

In September 1950, the Oregon and Washington highway departments chose a replica span just to the west of the original bridge. By the end of 1952, most of the major details were finalized: The bridge was expected to cost $11.2 million and it would be partially funded by tolling.

The return to tolling was an unpleasant thought to many, but it was clear that it was likely a necessary source of funding.

“From this end, it looks like a good deal,” The Columbian wrote in an editorial.

Enlarge

The Columbian archives

Legislature, lawsuits and tolling

In early 1953, Oregon and Washington lawmakers began asking for the Washington Toll Bridge Authority to join the Oregon Highway Commission to build the proposed span.

But the effort faced a hurdle when Washington State Auditor Cliff Yelle filed a lawsuit arguing that tolling on the bridge violated the agreement between the state and Clark County that after the state acquired the bridge and tolls were removed in 1929, the bridge would remain toll-free forever.

It was unclear if Yelle was against the project or if he was attempting to remove a hurdle before it had the potential to become barrier. But in a Columbian editorial, the newspaper wrote that “Yelle, it must be remembered, is not a judge and neither is the attorney general, so that legally his remarks are nothing more than a layman’s opinion. But presumably he had legal advice, and the lawyer may have sized up the situation correctly.”

The lawsuit made it to the state Supreme Court in September, and in November the court rejected Yelle’s argument by a narrow 5-4 decision. With the lawsuit out of the way, construction on a new span could start shortly.

After the lawsuit, it was also decided that tolls would not be imposed until work was completed.

The program hit a snag in July 1954, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, having received complaints from towboat operators, labeled the original span an obstacle and a hazard to navigation. Essentially possessing veto power over any new bridge, the Corps wouldn’t approve a second span until its concerns were addressed.

The solution came in the form of two humps, one for the new span and another added as part of a retrofit to the original, along with a 530-foot opening under the bridge allowing for most river traffic to pass under the bridge without requiring a lift as well as lessening the hazards that the towboat operators cited. Estimates projected that the retrofit of the original span would cost an extra $1 million.

The proposed two-span bridge was expected to have a capacity of between 75,000 and 80,000 vehicles a day — today 130,000 vehicles cross the bridge on the average weekday — and was expected to be complete by mid-1958.

Enlarge

The Columbian archives

Construction

Near the end of March 1956, Union Securities purchased the initial $9.3 million bond issue to finance construction of the second Interstate Bridge. The bonds were expected to be paid off through tolls.

As preconstruction and eventually construction on the bridge started, the thought of returning to tolls was distasteful to many, and with Congress poised to pass the Federal-Aid Highway Act, which built the Interstate System (In 1957, the bridge became part of the then-new Interstate 5), there was hope that federal funds would be available and could avert a return to tolling.

The idea was popular and seemed possible, and eventually the Oregon and Washington Highway Commission joined the push to remove tolls from the bridge.

U.S. Rep. Russell Mack, who represented Vancouver, said that the new span stood a strong chance of receiving federal funds thereby eliminating the need for tolls.

Although the bill was signed into law on June 29, 1956, the conversations around tolling simmered until late 1957, when the Vancouver City Council passed a resolution calling for the Interstate Bridge to be built using federal funds, eliminating the need for tolls.

The effort snowballed with leaders and elected officials in both states calling for the bridge to remain toll free. Secretary of Commerce Sinclair Weeks responded to the movement by saying that although the project is eligible for federal funds, it is dependent on Congress.

Washington Sens. Warren Magnuson and Henry Jackson introduced legislation in January 1958 to keep the Interstate Bridge toll-free, but the bill died in committee.

Oregon Senator Richard Neuberger placed the blame on Washington State Highways Director W. E. Bugge, as he was not persuasive in convincing the Senate Public Works Committee that the highway departments “acted with wisdom in floating the bonds for the bridge on the eve of Congressional passage of the highway bill, which would have authorized the bridge for 90 percent federal aid.”

Although the prospects for a toll-free bridge practically died there, many in Washington and Oregon held out hope for a miracle.

As construction of the new bridge progressed ahead of schedule, some worried that the new hump would be a hazard in winter weather, succumbing to ice and causing accidents and traffic jams. The worries caused the Vancouver Traffic Bureau to urge for the hump to be heated to prevent icing. The Washington State Highway Department quickly nixed the idea as the cost was too high.

Like with the construction of the first span, work conditions on the second span were dangerous. Two workers died. One fell to his death after the section of scaffolding he was standing on broke in 1957 and another fell while painting the bridge — his body surfaced in Kalama over a month after he died — in 1958.

After the first worker died, work on the bridge was deemed unsafe by the union. Members threatened to stop work unless the safety violations were corrected.

The new span opened in July 1958 to a celebration that resembled when the bridge first opened in 1917, from the World War I-style cars to Mary Helen Kiggins and Eleanor Holman, now adults, cutting the ribbon and officially opening the new span to traffic.

Work remodeling the old span started two days after the new one opened, but less than a week after construction started, an engineer strike caused by a failure to reach agreement with the Associated General Contractors led to work being brought to a standstill. The strike lasted about two months until they reached an agreement with the Oregon governor and did not seriously affect or delay construction.

Riding a bike across the bridge was temporarily prohibited after a Vancouver rider died after he fell off the walkway and into the path of a truck. The prohibition was lifted after additional guardrails were put in place.

The toll collector booths were erected in October 1959, leading to one Columbian reporter to liken them to “hangman’s scaffolds” where “the victims in this case will be strung up by their pocketbooks instead of their necks. As surely as death and taxes, the tolls will be collected.”

The original span reopened on Jan. 8, 1960, to no fanfare or celebration. Its opening marked the final defeat for the numerous people and parties that fought for it to remain toll-free. Tolls on the bridge went back into effect on Jan. 11.

Tolls cost 20 cents per car, 40 cents per light trucks and 60 cents for heavy trucks and buses and could be paid with cash or by toll token.

“Now Russia has its ‘Iron Curtain,’” The Columbian remarked, “Asia its ‘Bamboo Curtain,’ and Vancouver-Portland have a ‘Toll Curtain.’”

Enlarge

The Columbian archives

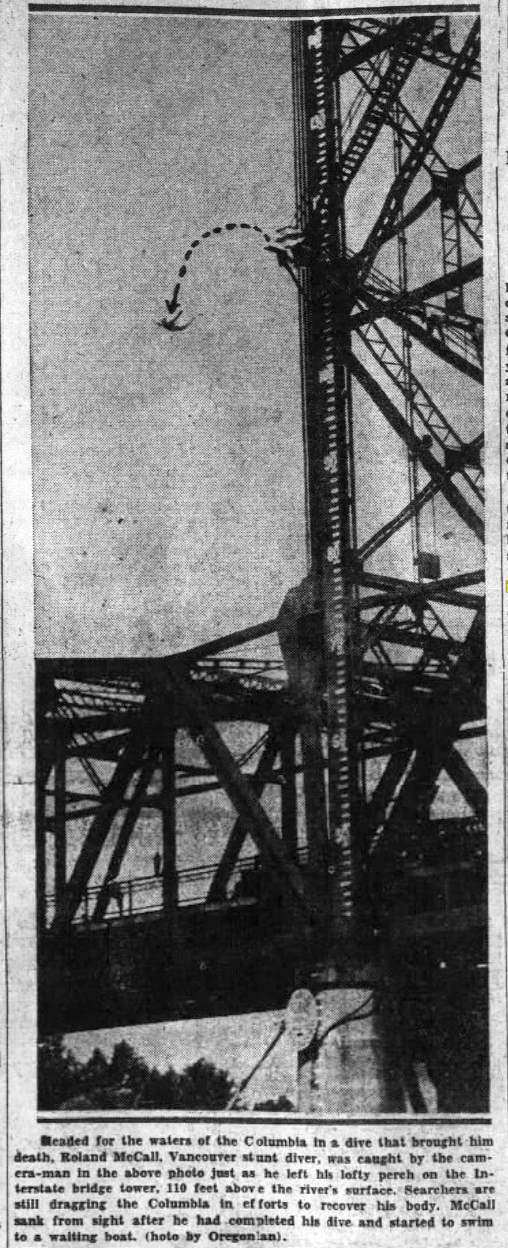

Swan dive ends in tragedy

Nina Goodrich watched anxiously from the bleachers as her son, Roland McCall, 27, climbed up the Interstate Bridge for what was scheduled to be the star attraction of the 1934 Independence Day regatta.

From Vancouver, McCall was a standout swimmer, he won nearly every event he entered, eventually being crowned the “city champion.”

He also saved two girls from drowning off Hayden Island in 1930.

He was also known as a daredevil. For the same event the year prior, McCall planned to dive 200 feet off the top of the lift tower into the Columbia, but Regatta officials nixed the idea forcing McCall to settle for an 80-foot dive off the bridge instead.

This year, 10,000 people packed in to watch him do a 110-foot swan dive into the Columbia. Goodrich was terrified of what might happen.

If McCall was scared, he didn’t show it. “(T)hey’d think I was a coward,” if he refused to take the plunge, Goodrich remembered her son saying.

As McCall’s feet left the green bridge and he entered into a perfectly executed swan dive into the Columbia below, the crowd wailed.

“Roland made the most beautiful dive,” Goodrich, then 95 and who lived to be 108, said in a 1980 interview with The Columbian. Upon hitting the water he momentarily popped up before disappearing.

The cheers quickly fell silent.

Crews and expert scuba divers searched for McCall in the days and weeks that followed to no avail. It wasn’t until 47 days after the regatta that his body was found washed ashore. It was assumed he had been beached for about two weeks.

“It tears you to pieces.”

Enlarge

The Columbian archives